“If 1,000 years from now archaeologists happen to dig beneath the sands of Guadalupe,” the director teased, “I hope they will not rush into print with the amazing news that Egyptian civilization…extended all the way to the Pacific Coast.”īy 1982, Brosnan had graduated from film school and was earning a living as a freelance journalist, but he couldn't shake his friend's story. But then his buddy pointed him to a line in DeMille’s posthumously published autobiography. “If 1,000 years from now archaeologists happen to dig beneath the sands of Guadalupe,” the director teased, “I hope they will not rush into print with the amazing news that Egyptian civilization…extended all the way to the Pacific Coast.”īullshit, Brosnan thought. When the shoot wrapped, the tempestuous director supposedly strapped dynamite to the structures and razed the whole set, burying it in the sands near Guadalupe, California, to ensure no rival director could benefit from his vision. The production nearly ruined DeMille and his studio. The set had required more than 1,500 carpenters to build and used over 25,000 pounds of nails.

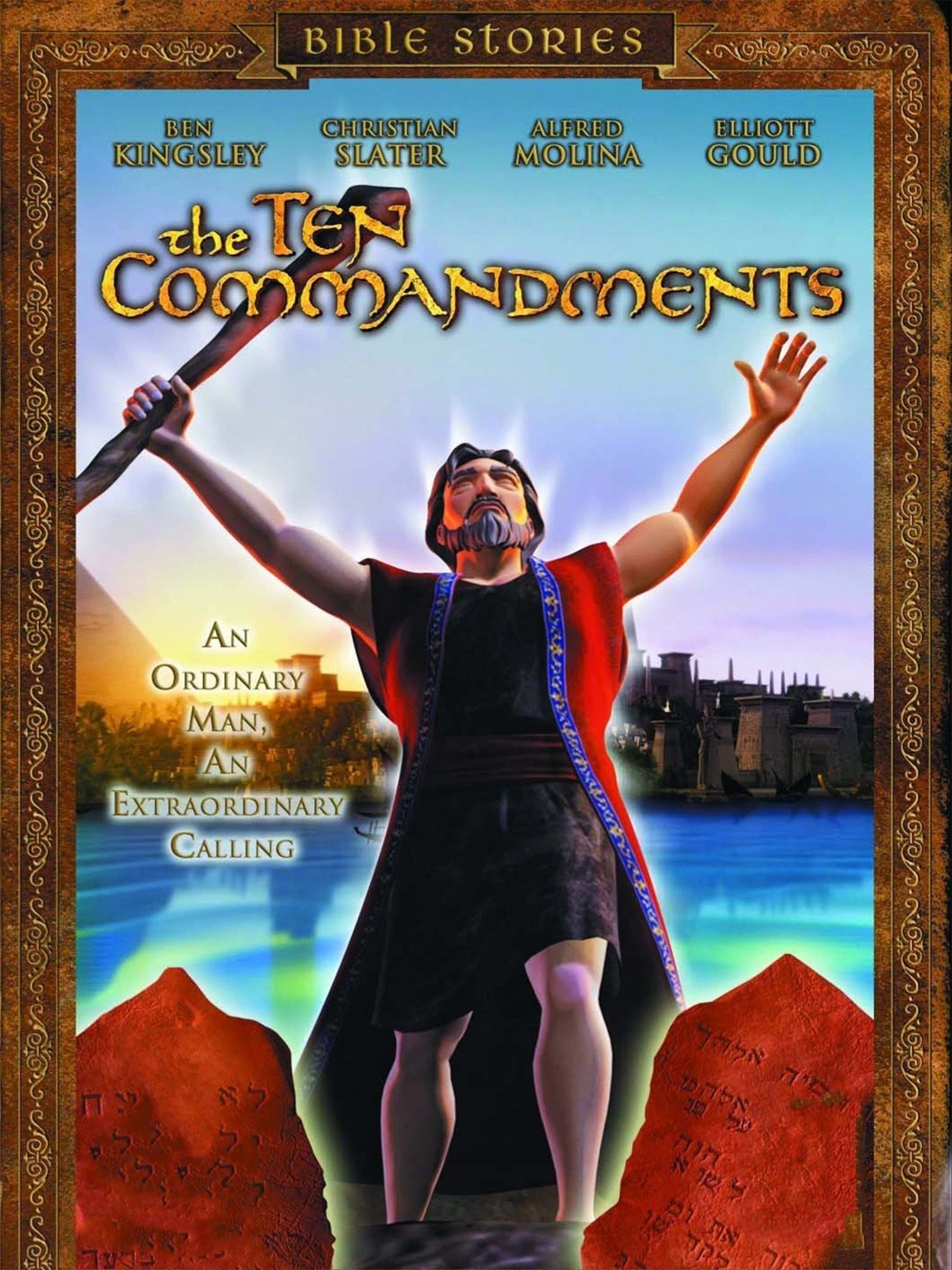

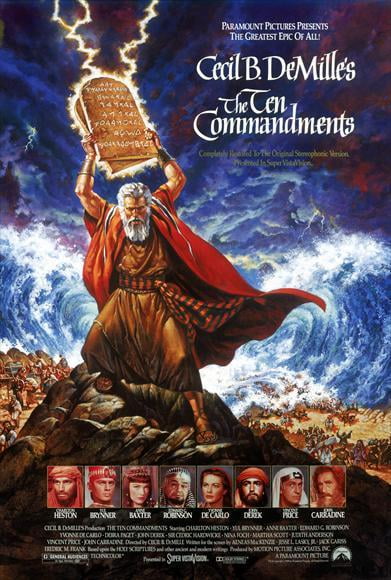

The faux Egyptian scenery had played the role of the City of the Pharaoh in one of Hollywood’s first true epics, Cecil B DeMille’s 1923 film The Ten Commandments. They were the 60-year-old remains of a massive Hollywood set-the biggest, most expensive one ever built at the time. “I thought he was nuts.” The ruins weren’t authentic Egyptian ones, of course. “It was an absolutely cockamamie story,” Brosnan says. According to his friend at New York University’s film school, the remains of a massive Egyptian temple, a dozen plaster sphinxes, eight mammoth lions, and four 40-ton statues of Ramses II were all supposedly entombed in the sands 150 some-odd miles north of Los Angeles. Thirty-three years ago, Peter Brosnan heard a story that seemed too crazy to be true: buried somewhere along California’s rugged Central Coast, beneath acres of sand dunes, lay the remains of a lost city.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)